I’ve been meaning to discuss some of C.J. Cherryh’s novels in the QUILTBAG+ Speculative Classics series, but I was unsure where to start. Then I realized that her Chanur space opera series was included in my pre-2010 neopronouns in SFF list, and I’d eventually like to review all titles on said list. Even if the pronouns turn out to be a minor part—which sometimes happens with these older works—it is still likely for these novels to contain some sort of interesting approach to gender.

This was indeed what I found, in this particular case. The first volume of the series, The Pride of Chanur (1981) does include neopronouns: specifically the stsho, one of the non-human species in the narrative, use the pronoun gtst. “The stsho proffered delicacies and tea, bowed, folded up gtst stalklike limbs—he, she, or even it, hardly applied with stsho—and seated gtst-self in gtst bowlchair, a cushioned indentation in the office floor.” (p. 13)

The stsho also have three sexes: “Methodical to a fault, the stsho, tedious and full of endless subtle meanings in their pastel ornament and the tattooings on their pearly hides. They were another hairless species—stalk-thin, tri-sexed and hanilike only by the wildest stretch of the imagination, if eyes, nose, and mouth in biologically convenient order was similarity.”(p. 12)

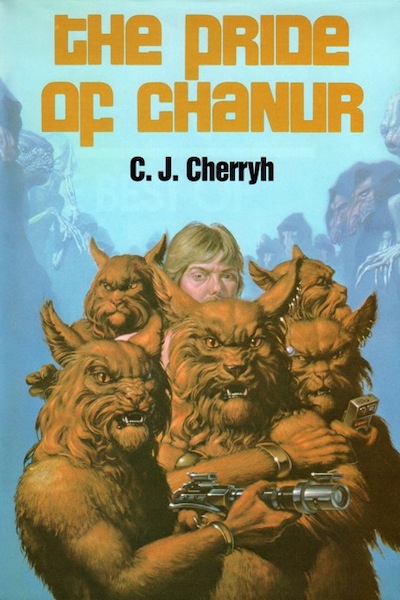

As we might already see here, the stsho are vaguely queer-coded, but they also play little part in the plot of this novel; this might change in the sequels. Instead, the story centers on the hani, fur-covered sentient beings most comparable to lions. (The “pride” in the title thus becomes ambiguous—is it about the emotion, or the group of lions? Most likely both.)

Pyanfar Chanur, captain of the spaceship The Pride of Chanur, faces a series of difficult decisions after a strange hairless creature runs onto her docked ship on a busy space station. Pyanfar and her crew soon realize the creature is sentient and capable of speech, but as they try their best to communicate, it turns out that this male of a so-far unknown species has escaped from the kif—another member species of the trade alliance called the Compact, alongside the hani. Pyanfar refuses to surrender the so-called “human” to the kif after the human claims to have been mistreated by them. An enormous mess ensues, with the fate of the Compact itself on the line…while Pyanfar also faces danger on a personal level, as the Chanur are embroiled in a battle over family succession.

Cherryh explores multiple aspects of this setup in detail. Various plot points emerge from the communication difficulties not only between the lost human and the hani, but also between different Compact member species. I especially liked that the setting featured automated translation, but it still needed initial data to be fed to it to approximate even a rough translation, which required effort from the characters. It was also interesting to see that there was also a trade pidgin between some—but not all—of the Compact species despite said automation. But for the purposes of this column, it’s probably more relevant to look at how Cherryh tackles gender, sex, and biological determinism in the novel.

It is only the women of the hani who travel in space. All ships are gender-segregated. The men are considered too erratic to go to space and behave themselves there; and indeed, they do spend a lot of their time physically fighting each other for dominance back on their home planet. But—and here I’ll have to discuss some developments in later chapters, though I won’t spoil the overarching plot—this strict biological determinism is undermined by Pyanfar Chanur herself, who finds herself wondering if said differences in gender roles are innate, or due to upbringing.

I don’t know if I should call this a genderswap when there is so much variation on our own Earth in these kinds of roles. In one of my own cultures, it was traditionally the women who traded and made a living, though for a different reason than the hani: the men were busy with their religious duties. Maybe I could say that the hani are a genderswap of many Anglo-Western cultures, though this would also be an oversimplification: Cherryh crafts her world with her trademark sense for nuance and detail here as well as in her other novels. This is the type of space opera where you find out exactly how docking clamps work, and that also extends to social aspects beyond the technological, like gender roles.

Humans still seem to be humans, and their own ideas about gender affects how the hani who come into contact with them proceed to think about their own gender. This is done in a surprisingly gentle way, with Tully the escaped human modeling a kind of masculinity that is as far from toxic as possible, while the narrative also affords him room for vulnerability as someone far from home, an outsider cut off from anything familiar.

There’s something intriguing about the premise of a crew that’s single-gender for reasons of chastity (and again, I’ll need to go into a bit more plot detail to discuss this point). When speculative works include this arrangement as part of the plot, I tend to expect the intent to be subverted by showing that same-sex attraction exists. This is what I expected here, especially in a work which already had neopronouns and an interesting approach to gender. But what happened in The Pride of Chanur was altogether different: the presumably-straight man ends up on a ship of straight women, and they all decide to be professional about it and not act on any potential desires. (Despite the difference in species, the question does present itself—at one point, the captain worries that one of her crewmembers might start a liaison with the human.)

I found this approach refreshing and it poked against my own preconceptions of what a gender-conscious science fiction book should look like, alongside the portrayal of human masculinity. Is the reader expecting Dudebro—because he is a dudebro, not just a man, but a specific kind of man—to do something catastrophically awful? Most likely, yes. The entire crew certainly expects him to do just that. Captain Pyanfar herself considers this repeatedly, treating the human with caution, and only allowing him increasing leeway by small increments. Does the reader expect some of the women crewmembers to be attracted to each other? Maybe not in 1981 (though I’m not sure about that—the trope existed at that point), but today, definitely so. This doesn’t happen either, and yet gendered aspects of the setting have been destabilized in a way that is deeply feminist. This is much less apparent on the surface than the three-sexed aliens with their neopronouns, who we sadly don’t see much of in this novel, but is more impactful structurally. It also enables Pyanfar to examine her own biases, and act on her realizations.

A final note: when I showed the first draft of this review to my spouse R.B. Lemberg, they asked me if I knew whether Cherryh was reacting to Larry Niven’s Kzin stories, which feature catlike aliens who are extremely male-dominated. I’m honestly not sure if this is the case—I looked and I’ve only found fans comparing these works, but no discussion or statement directly from the author.

I’m very much looking forward to seeing where Cherryh takes the series next—the following three books form a trilogy, and I’m hoping to cover them in my column as well. They will be interspersed with standalone works by other authors—for next time I have a novel queued up that won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. I’m also considering covering more Cherryh after I’m finished with the Chanur books: do you have any particular favorites?

Please cover more of these books. The Compact is such a compelling piece of sci-fi especially given the tumult taking Kim, Pyanfar’s husband, onboard. The fourth book also delves deeply into what I have always sought after in human/alien relationships and especially the entitlement one may feel when they’re attraction goes unrequited or can’t be fulfilled. A shame there weren’t more but what’s there is compelling character driven goofs.

You’ll learn more about the stsho in Chanur’s Legacy, the 5th (and so far, final) book in the series. Not only are they tri-sexed, but their gender is much more fluid in comparison to their biology (which also shifts natively with gender identity). Only one of the three stsho genders talks to outsiders, the gtst. High stress can cause a stsho to shift genders, which may cause them to become secluded, and hand off delicate negotiations to another.

This series takes place on the opposite side of human explored space from her Alliance-Union universe, which also has some fascinating takes on gender and queercoding and gender roles. I’ll note that early Cherryh very much has a lot of “sexually abused male” characters through roughly the late 1980s.

One of the incredibly subtle things about Pride of Chanur happens when they’re on the Hani homeworld, and its about how Pyanfar, in worrying about her husband (and the lord/pet of the Chanur estate), reverts completely to her native sexist attitudes about male Hani. And when he doesn’t “act down” to her expectations (but does fulfill his traditional role!), she lies to herself to avoid self-admission that her expectations had dropped.

Having an alien character lie to themselves to avoid admitting that they’d thought the worst about a different gendered member of their family is one of those things that’s incredibly easy to miss when reading the book the first few times. (I brought it up with CJ at a reading a dozen years ago, and she laughed, said that yes, it was intentional, and it was something very few people had spotted in the 25 years since the book had been published)

It’s worth noting that *large* chunks of Anuurn (the hani homeworld) are given over to reservations where males basically run wild, and when hani females get the itch, they go to the reservations to get laid, possibly get pregnant, and possibly convince a likely hani male that it’s time for him to challenge the current head of her household, who’s getting old and might lose a dominance challenge melee. It’s implied that the current female residents of the estate will equip the current lord, and any juvenile siblings, and then they’ll “go do boy things, we’ll patch up the survivors and make him lord.” The females don’t participate in the contest, any surviving males on the losing side are sent to the reservations, and there’s an adjustment period.

It’s considered a black box for cultural reasons, not biological ones, and the attitude of the females towards the males is that they’re to be cherished and feted while they’re in the household, that adolescent males are often shuffled off to allied households where the male has gotten…old or insane or toxic, to do a challenge to remove an unfit male. There is an *implication* that the reservation system is a cultural accomodation to avoid the problems of new male members of the household killing the male children of the old lord, and that it’s very recent, and has some conservative pushback.

It’s implied that the vast majority of hani art (ballads, songs, novels, paintings, sculptures, erotica) is created by males for female consumption and trade, and that the sign of a well run household is one where the male head of house is both aware of his gender roles, and strong enough to deter constant challenges, so that he has the liesure time to make art, which is both a trade good and a status symbol.

The traditional hani male “led” household fiction is completely set aside when coalitions between houses or amphinctonys regulating scarse resources, or piloting starships.

Hani gender dynamics are explored in more detail in the middle three books of the series.

It should be noted that the hani were based off of then-current knowledge of how prides of lions lived in Africa; they weren’t a deliberate counterreaction to Niven’s Kzinti, and gender relations among the Kzinti are only touched on en passant until the Man-Kzin Wars shared universe novels of the late 1980s. Probably to our great benefit, to be honest. Niven is _awful_ at gender dynamics.

, which also has some fascinating takes on gender and queercoding and gender roles.

Has it? I can’t say I noticed it, although I haven’t read Cyteen or 40,000 in Gehenna.

Think about Signey Mallory’s….relationship…with Joshua Talley in Downbelow Station. Ari Emory in Cyteen (and her ‘murder mystery’ plot) are, in many ways, her embracing of the cultural mores of Union and its use of azi, who are absolutely coded as queer male (and thus ‘safe’ and ‘non-threatening’ to the Strong Female Characters Who Don’t Have Time For Your Masc Bullshit that CJ threw through the series.)

CJ married Jane Fanchar a bit over a decade ago. Jane moved in with CJ as a housemante/ collaborator in the ’80s, as CJ’s parents retired to assisted living. It’s…notable…that after Jane moved in that a lot of CJ’s “how do you like it when it’s done to you.” male character portrayals just kind of stopped happening.

Think of CJ as being a very smart gay woman, afraid to come out as gay in Oklahoma in the 1980s in her 40s, especially when she was a high school teacher for years, quietly got her gay paramour to move in…and suddenly didn’t feel as much social pressure to conform and explain the lack of a husband to her parents.

It’s queer coding, but it’s the queer coding of a woman living closeted in a conservative part of the country, trying to figure out how to do it at ALL.

Having re-read Cyteen within the past month, the azi are autistic-coded and when they’re queer it’s not even coded: Grant (azi) and Justin (citizen) are both probably bisexual at least in their teens but after going through the trauma of the first third of the book together they settle down with each other and a psychiatrist asks obnoxious questions about whether Justin’s partnership with Grant is due to queer dads or trauma. They could be gay, could be monogamous, but definitely queer and not in subtext.

(Evidence for bisexuality: Grant reports back on the unfairness of having to say “No, sera, I can’t” when a cit girl his own age proposes to go beyond heavy petting; in the same commiseration session Justin cherished hopes of getting together or at least off with a cit girl his own age only to learn that she wanted to date/etc. handsome Grant.)

Justin’s cit father and his azi partner are the model of gay dads although Jordan had an affair with a woman in his youth and it didn’t go well for many reasons but it’s stated that one of the reasons was that he wasn’t het.

Now for azi engaging in heterosexual sex. Azi aren’t supposed to have sex with any cit who’s not licensed to Supervise them; Florian II’s perspective tells us that azi would get a tape flash warning them against having sex with at least some unsuitable other azi. Ollie (azi man) is involved with Jane Strassen (cit woman). Ari II’s azi security team both have fade to black or disappeared to the bedroom together heterosexual sex with each other and with cits. Eventually Ari II’s friend Amy (cit) gets matched with an azi man as a partner and assistant, after some cit dating disasters and envying the arrangement Ari had with Florian.

Like I said, I haven’t read Cyteen and can’t comment on it. The Strong Female Characters Who Don’t Have Time For Your Masc Bullshit were already becoming a trope when those came out, but I never read them as queer coded, then or now, because they kept having sex with men (which some queer women do, granted, but that’s not really the point). Also because they remind me of some of my girlfriends from when I was presenting male back in the day. Granted your point about her environment, though; I was fortunate enough to never have been forced quite that deep into the closet.

The book I always suggest to first-time Cherryh readers is Merchanter’s Luck. A recent rereading did not find any gender-specific role-setting — how far you got in a large ship’s hierarchy depended on how good you were — but it continues the trope of a relatively secure woman (although young enough to be not nearly as powerful as Morgaine or Pyanfar) and a man on the edge, as established in the Morgaine books and continued in the Pride books. (The naming is deliberate; Morgaine is the last of a crew that set out to patch holes in the universe, while Pyanfar has a crew behind her.) I didn’t find any queer-coding in it, but that’s not something I’m especially sensitive to. The one caveat I reached after the latest rereading is that there is a lot of backstory that comes in compact scattered nuggets; it’s not critical to the story if you can accept that the man is behaving relatively rationally (a stumbling block for one person in my book group), but first reading Downbelow Station (a thicker book in several ways) would make it easier to understand the man’s desperation. You might want to start with Downbelow Station since it sounds like you haven’t been put off by the density&intensity of Cherryh’s language and plotting (then read Merchanter’s Luck for fun); ISTM that reading books that are chronologically a bit earlier (e.g. Heavy Time) doesn’t win, as Downbelow is where she introduced the conflict.

Not by Cherryh, but as far as the theme in general I’ll suggest some of Bujold’s Vorkosigan books. In Shards of Honor the first book, one of the protagonists is bi. In The Warrior’s Apprentice , (arguably also the first book, if Shards is considered a prequel) a third gender of human is introduced, and Ethan of Athos is the first book I ever read whith a gay protagonist whose idea of a happy ending is a husband and lots of kids who has absolutely no angst, trauma or issues with regards to his sexuality, and who, at the end of the book, gets to introduce the nice boy he met out in space to his dads, and they settle down to raise a family together. All these were written in the early 80s and published throughout ’86.

ISTM that Ethan is a poor example, because Athos (named after a notorious monastery) is a world of men who have been taught to believe women are ~demons; being gay is the default rather than a minority position, so it can’t be a source of angst. I suppose it gets props for denying that being gay is “inherently disordered”, and for having a somewhat less deceitful society than Chandler’s Spartan Planet, in which everyone but the ~priesthood is taught that they reproduce by fission (which all the native fauna do, so the descendants of the Terran colonists don’t even think there’s another sex), but that’s not a high bar.

ISTM you weren’t a queer kid in the 80s, because trust me, in 1986 (and three years later in ’89 when I started readind the series) the idea of a society where being gay is the accepted norm was revolutionary. I’m not going to say it’s without problematic elements, but neither is anything else, especially back then. Keep in mind that the article we’re commenting on made it on the list purely by virtue of a side character of a species different to all the protagonists and with whom they can barely communicate has a different sex/gender system that nobody else understands at all. With that as the benchmark for representation, Ethan (and Bel Thorne; I know a lot of folks in the community disapprove of the term hermaphrodite and the pronoun it these days, but the moment I met Bel Thorne I knew what my gender was, and so it remains to this very day) was the brightest star in the firmament. At that time, I could count on the fingers of one hand all the books I’d seen that even mentioned the existence of queer people, let alone in a positive/accepting context.

In the mid-1990s when I finally got introduced to the Vorkosigan series, I clung to that “was bisexual” in Barrayar with a vicious pride: it was a safe space for an insignificant bisexual teen, because even though she was using the past tense, it wasn’t a space that wanted to erase people like me. It wasn’t safe to be out on Barrayar? Whatever. It wasn’t safe to be out on Earth here and now. And there was a whole planet where I could not only be out safely, but I could be effortlessly out to everyone I met, just by wearing the correct earrings.

Regarding other Cherryh books to read, she is certainly prolific, and covers a wide range of subjects (her fantasy books are somewhat overlooked I think, and while she hasn’t written much short fiction, it’s worth reading). Her style changes over time to become less dense, she will happily spend a chapter in her later books where the characters just drink tea. So it depends on what you like to read, and how much time you have. After you finish the Chanur books I think it would be fair to read Downbelow Station and Cyteen (both Hugo Award winners), then some fantasy, perhaps The Dreamstone, and at least the first of the Foreigner books (not my favorite of the series, but a good place to start). Then if you have time, swing back and read some more of her early works, like Gate of Ivrel (note the Michael Whelan cover that is a gender swapped version of your typical sword and sorcery cover), and The Faded Sun: Kesrith.

For added enjoyment, there’s the filk classic “Pride of Chanur” [lyrics below the video]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEBVNVcAXhU